Today, fairly rigorous testing in the pre-production stages of new artist materials, including accelerated ageing tests for new pigments/paint films, helps to ensure that conservators of contemporary art have at least some idea of how potentially never-before-used pigments might age/deteriorate in the near and far future. However, should one automatically assume that paintings created in the 20th – or even 21st – Centuries will necessarily use pigments or paint films that last longer than paint made in the 17th, 18th or 19th Centuries…?

The professional focus of fine art conservators means that for much of the time, they are approaching a work of art from a material point of view. This demands an excellent understanding of the properties of the different component parts of an artwork. For painting conservators, this includes the various pigments used in the paint film that is applied to the substrate.

For example, we know that YInMn (Yttrium, Indium, Manganese) Blue, the first new inorganic pigment created in over 200 years and only licenced for use in artist paint in 2020, is more stable than a lot of other blues, with good lightfastness, and good opacity when in a paint film, and also good permanence. We also know that it is less toxic than blues that use the pigment Cobalt, which incidentally was the last inorganic blue pigment to be created before YInMn (all the way back in 1802).

This knowledge is enormously helpful for conservators, who in the past have faced certain challenges when treating paintings incorporating materials that are little used in art; and therefore, little studied and potentially barely taught on conservation training programmes (think of the first generation of conservators to treat house paint, as opposed to more conventional artist paint?)

Greater accumulated knowledge and research is of immense benefit, to say nothing of the debt owed to artists themselves – many of whom throughout history have campaigned for higher-quality artist materials. In the post war period trail-blazing artist Gluck (1985- 1978) largely put her own career as a painter on hold to devote herself to a prolonged campaign for artist paints to be produced to a far higher standard.

However, should one automatically assume that paintings created in the 20th – or even 21st – Centuries will necessarily compromise pigments or paint films that last longer than paint made in the 17th, 18th or 19th Centuries?

Fluorescent pigments, which only started to be commonly used by artists from the 1960s onwards, present numerous challenges to the conservator. Namely, how best to slow down the inevitable and irreversible fading of the fluorescence.

The reality is that even if optimally displayed and conserved, the first signs of intensity loss to the fluorescence are likely to be visible after a mere five years. Though even here, documenting the fading of UV pigments is difficult as the photographic conditions must be exactly the same to ensure that the colour is calibrated to show change.

For artworks that incorporate fluorescent pigments, preventive conservation is critical. For example, for paintings intended to be displayed under UV light, one popular approach is to present the painting in a dark room with a sensor-triggered lighting system to trigger the UV needed for the work to be best appreciated only when spectator approaches the work.

UV light not only poses preventive conservation issues, but also certain complications should they ever require restoration work. How to successfully retouch a painting meant to be shown under UV-light (famously the tool used by conservators and art appraisers to highlight retouching, which may be invisible to the naked eye), is a challenge that many conservators of fluorescence have to grapple with.

Whilst a recent creation date is no certain guarantee of longevity, the stringent testing stage that new pigments / paint films undertake in the pre-production stages is of enormous benefit to conservators, given the length of time it has taken in the past to build up the necessary knowledge to preserve and restore what were then potentially new or little studied paints and pigments.

As we start to see more paintings created with YIMn-based paint, it will be interesting to see what challenges (if any) its properties pose for future paintings conservators.

Some advice on Selecting Paint from the ASTM and Lightfastness of Media American Society of Testing and Materials (ASTM)

• Art material manufacturer websites are an excellent resource for information on lightfastness as an increasing number of companies are now publishing the lightfastness results of their products based on the tests outlined above.

• It is important to note that the lightfastness of a particular pigment can differ with the vehicle used. For example, Vermilion has a lightfastness rating of I (excellent) when mixed in oils and acrylics. However, in a watercolour vehicle, it has a rating of III (fair). For this reason, one should check the lightfastness rating for both the specific manufacturer and the medium.

• One should always check the label on a tube or jar to see if the generic names of the pigments are used and if the manufacturer certifies that the paint conforms to a standard and lists the lightfastness rating of the paint.

More from the Blog

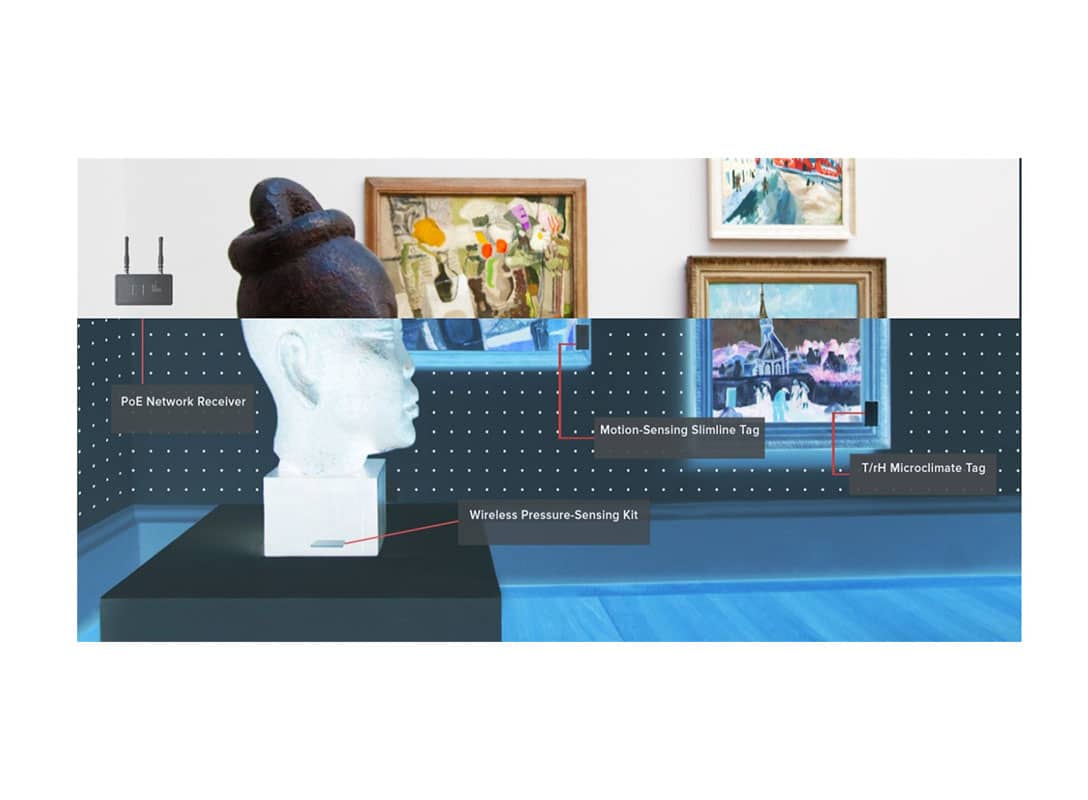

Time to Upgrade Your Art Security?

Post Covid-19 – What Next For Auctions?