We have recently been posting on Instagram and LinkedIn about our involvement in the Islamic Arts Biennale in Jeddah. Each week we picked an object, historic or contemporary, to share and added a little conservation insight about conserving specific object or generally addressing materials and their conservation considerations.

The biennale’s run was coming to a close and we realised that we had failed to highlight any of the fantastically detailed arms and armour that were on display from the Furusiyyah Art Foundation which our conservators had monitored in their daily rounds.

– Islamic Arts Biennale 2025, Photo by Marco Cappelletti, courtesy of the Diriyah Biennale Foundation

We asked our metals conservator Hal for some insights into his experience conserving arms and armour and swiftly realised that we had more than an Instagram post of information to share. So we are presenting here our interview with Hal exploring some of the nuances of metals conservation, corrosion and patination through the lens of historic arms and armour.

How do you approach conservation of arms and armour like the helmets and sword in this Islamic Arts Biennale photo?

In this photo here there’s chainmail on the helmet in the centre. Chainmail can lose links over time in some examples that I have seen. If the losses are wired together without the links being replaced then the shape is lost, like adding a dart in a piece of fabric.

We often come across historic restorations where the incorrect materials have been used, or and object has been repaired, or rebuilt in a limited way depending on the skills available at the time. E.g. stitching chainmail losses with wire as a stopgap, or quickly fixing it to the helmet if it had become detached, and never returned to / restored properly.

If the shape of the piece is wrong then it is open to misinterpretation. Further down the line if this was on display would a member of the public visiting know that the object was not displayed correctly?

Liaising with curatorial expertise is helpful in making historically accurate decisions on how an object should be presented. The aim is always for the objects to be presented, as they are at the [Islamic Arts] biennale, with every element appearing correct.

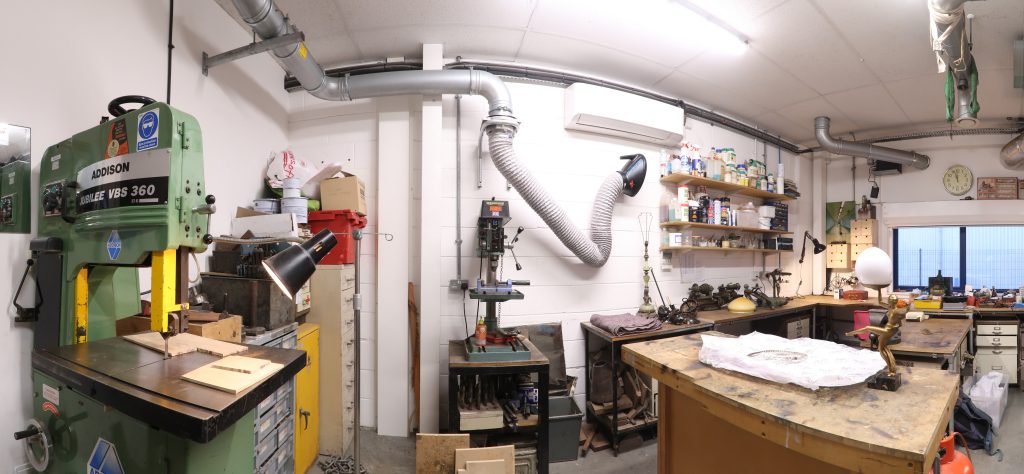

– A panorama of our metals conservation workshop

How often do you work with other conservators with different specialisms?

Often arms and armour have textile, leather and wooden elements so my work includes a collaboration with conservators specialising in these materials. A metal sword may fit into an ornate scabbard with a velvet cover, and leather straps. Armour was built up in layers with padding to make it more comfortable and to offer more protection to the wearer, all of these layers may be composed of a different combination of materials.

Mountmaking is also a key area that I work with, once the objects are conserved, the right mount allows it to be displayed safely and correctly.

Panorama of our metals conservation workshop 2

When metal objects come into the studio they might have any level of corrosion, and have developed a surface patina. When you conserve these items where do you draw the line between corrosion and patination?

It’s quite nuanced, it’s a topic in its own right that conservators have written extensively on. Technically speaking corrosion is any type of oxidisation on the surface of metal. Rust on steel or iron. Copper carbonate on copper or copper alloys of bronze or brass. It’s the copper that goes green.

By contrast, patination is either intentionally applied for example to a bronze sculpture. I’d never call that corrosion although it is the result of oxidisation. Patination can also be natural surface change that has developed over time. On iron and steel iron oxide is a dark grey, hydrated iron oxide or “rust” is a secondary reaction of water with the iron oxide coating.

A rusty iron or steel object is more susceptible to further corrosion as the crystalline structure of the oxide can retain moisture which can further the reaction. Although at the same time a rusted coating can exist as a form of protection. Thinking outside of arms and armour for a moment Corten steel used in architectural elements uses red oxide as a surface layer of protection and is appreciated for its decorative appearance.

- Corroded sword – The rusted hilt contrasts with the cleaned blade.

- Corroded sword – Before cleaning showing etched decoration on the blade

- Corroded sword – after corrosion removal showing preserved detail and some pitting in the surface

- Corroded sword – heavily corroded section before rust removal

- Corroded sword – heavily corroded section after rust removal showing significant losses

- Corroded sword – the remains of the scabbard that the sword arrived in. The fabric had held moisture in contact with the blade which accelerated the corrosion process.

An object’s use and history is important in the decision making process of when to conserve or remove patination. A ceremonial sword like the one above that has been in use since its creation and which has always been intended to have a bright shine could be polished back to its original brilliance. Archaeological objects on the other hand should never be cleaned back to that extent otherwise you’ll have lost centuries of a built-up surface.

A patina is seen as an intended or evolved surface that is seen as attractive, or wanted. Corrosion is seen as a more negative term. For example the green that develops on bronze over time is certainly a form of corrosion but when redefined as “Verdigris” has more venerable and positive connotations.

Active oxidisation vs stable oxide layers

[Speaking to a metal vice in the workshop] This is a good example, this steel vice surface has turned a nice sort-of grey colour, it has certainly oxidised but I would never say it was corroded. This dark grey colour is what you expect to see in well maintained mechanical objects and suits of plate armour. It is unusual really to see a bright steel surface as it very quickly develops this darker Iron oxide layer.

The time to remove corrosion is when it is active, “bronze disease” for example is a continuous cycle of corrosion where the product of the first chemical reaction creates a new compound that perpetuates the cycle. In the case of bronze disease and related cycles of corrosion this material must be removed before conserving the object. Then reviewing the objects environment is important before it is returned, to ensure the cycle does not start again.

Precious metals

Gold and silver elements in arms and armour can be especially satisfying when cleaning. Gold itself does not corrode but it can become covered in layers of oxide created by surrounding metals. Silver famously tarnishes but can polish back to a bright shine. Often when cleaning pieces with gold, or silver inlay it can be very satisfying to reveal the bright inlay among the patinated metals surrounding.

– A steel handle with polished silver inlay

To find out more about our metals conservation you can find case studies on our website of metal & mechanical objects, bronze restoration and silver & precious metals. Hal previously spoke with Family Office Magazine about how to care for outdoor sculpture.

If you would like any advice or a quote for conservation, whether it’s for one item or a whole collection, please send details of your object or project to info@plowden-smith.com