Reviving Mary Lanchester’s Portrait of a Boy — The Art and Science of Paper Conservation

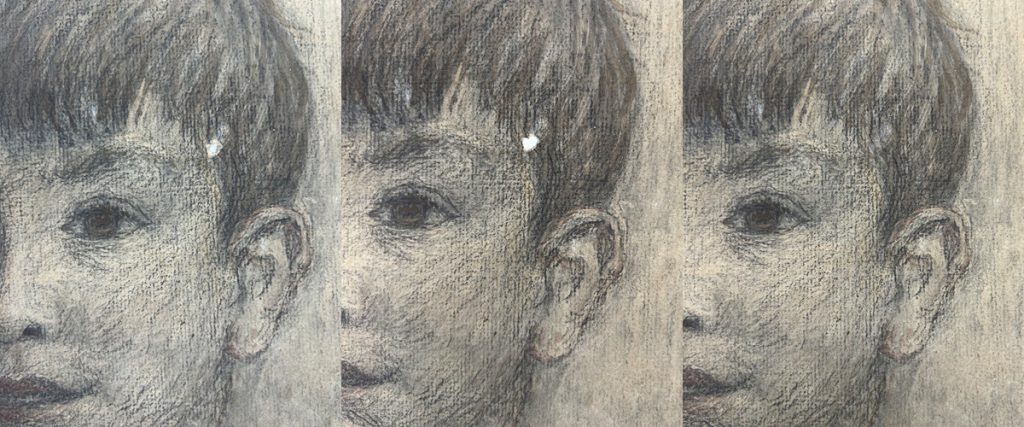

When visitors stopped by our stand at this year’s British Art Fair, they witnessed something rarely seen outside our paper conservation studio: the delicate, painstaking process of conserving a fragile work on paper. Over several days, as part of our live demonstrations, our senior paper conservator, Karina Lavings, began restoring a charcoal drawing by Mary Lanchester (1864–1942) — a mixed-media drawing in ink wash, chalk, charcoal, and pastel.

By the time of the LAPADA Fair in Berkeley Square, the treatment had been completed, and the newly conserved portrait was proudly displayed — a testament to both the artist’s skill and the subtle craft of paper conservation.

If we can help you with conservation of artworks, drawings, prints or historic documents please do not hesitate to contact us for a complimentary estimate and treatment proposal.

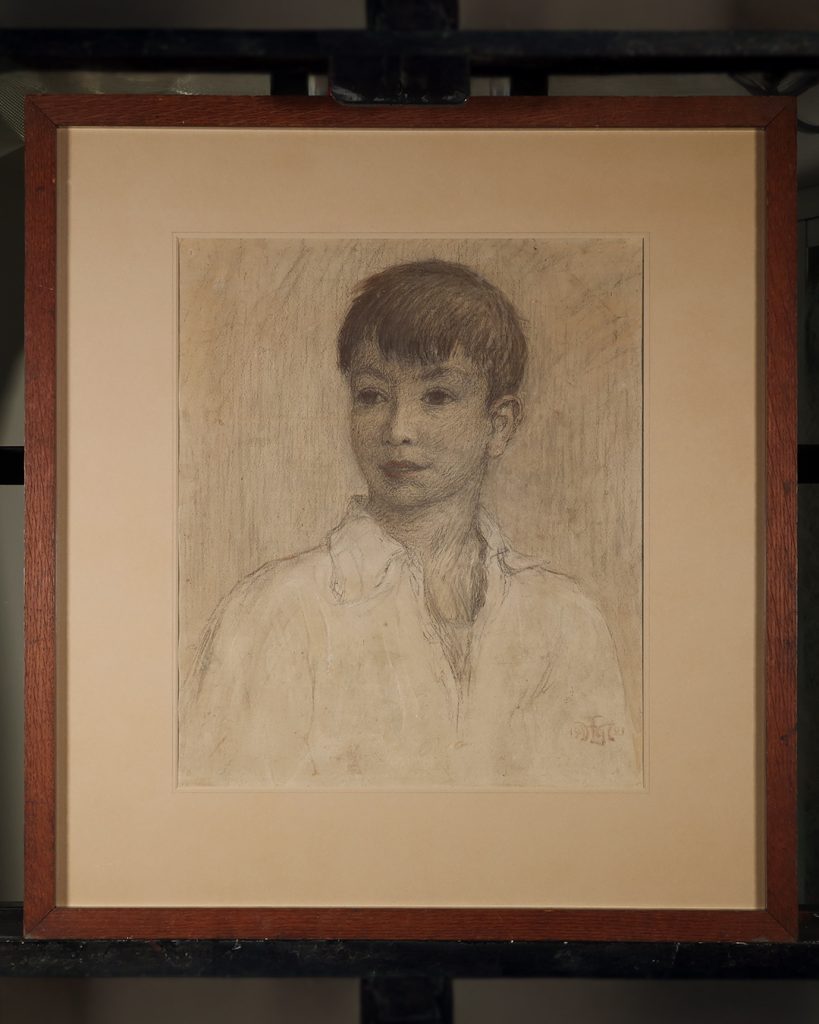

After Treatment – the artwork returned to its original frame in new mounting materials and museum glazing.

Condition: A Fragile Surface and a History Revealed

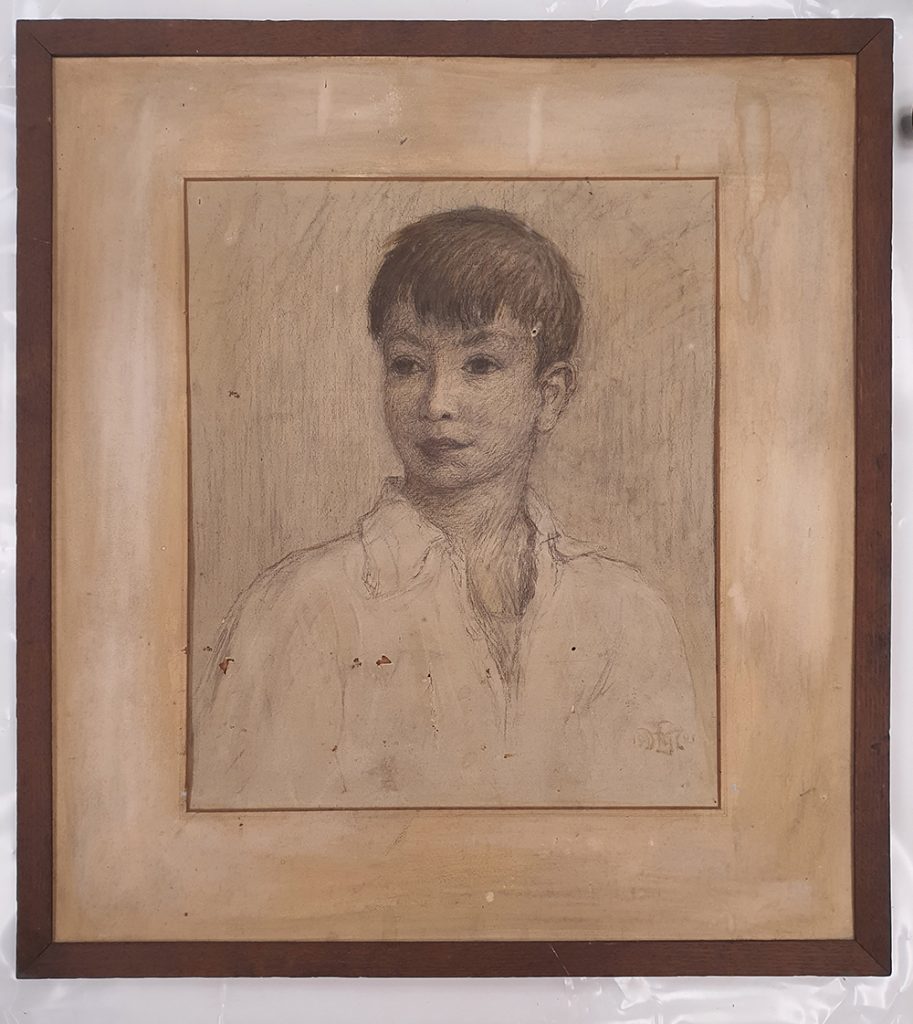

When the portrait first arrived in the studio, it was immediately clear that the work had suffered from years of environmental exposure and unsuitable mounting materials. The drawing was unglazed, leaving the surface vulnerable to dust, air pollution, and mechanical damage. The artwork showed significant surface dirt, small punctures, and evidence of historic insect activity.

The window mount bore signs of water staining, and the wooden backing board had warped allowing dust and moisture into the back of the framed artwork. A common problem in older frames is that wooden materials, frames and backing boards can cause acidic off-gassing (in this case, acetic acid) which can accelerate the paper’s discolouration and embrittlement.

Subtle planar distortions— gentle ripples or waves in the paper — had also formed over time. As Karina explains, “Paper is hygroscopic, meaning it absorbs and releases moisture depending on the surrounding humidity. Rapid changes in humidity cause the paper fibres to expand and contract, creating undulations in the sheet.”

These distortions, while often overlooked, can lead to further structural stress if not corrected and properly supported through flattening, and conservation mounting.

Before Treatment the original mount had a mottled appearance and the artwork has visible tears and marks.

The Treatment: Cleaning, Stabilising, and Respecting the Artist’s Hand

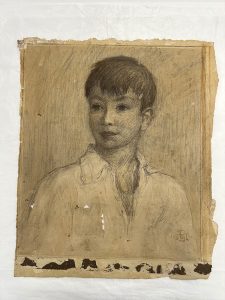

The conservation treatment began with the careful removal of the artwork from its frame. Loose surface dirt and insect debris (including traces of webbing) were lifted using a brush-vacuum, a gentle suction device that clears contaminants without disturbing the fragile media.

During Treatment – an initial clean before our conservation demo at the British Art Fair.

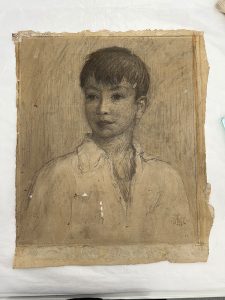

During Treatment – Careful inspection removing the artwork from the backing board.

A key challenge emerged early in the process: the drawing had been adhered directly to its window mount with an animal glue adhesive. This approach, once common, is now avoided because it can distort the paper and makes future treatments difficult — the artwork cannot be safely separated from the mount without risk of tearing or loss.

Karina mechanically released the drawing from the mount using a spatula and scalpel, softening residual fibres with a methyl cellulose poultice. “The goal is always to separate layers in a controlled, reversible way,” she notes. “We had to be careful to apply moisture only to areas of mount that were being removed, this avoided embedding surface dirt into the paper fibres of the artwork.”

During Treatment – the artwork mechanically released from its mount still had parts of the mount adhered to the artwork surface.

During Treatment – After residual mount removal using a a methyl cellulose poultice in our studio.

Because the artwork incorporates charcoal, chalk and pastel, all friable media that are not firmly bonded to the paper that supports it, surface cleaning of the image area itself had to be minimal. These materials can easily smudge or lift, so cleaning was confined to the sheet’s edges and the verso (reverse side).

Once cleaned, the sheet was lightly humidified — a subtle introduction of moisture that relaxes paper fibres just enough to allow flattening without risking pigment disturbance. This step enabled the paper to dry flat and stable under gentle pressure.

During Treatment – Gently humidifying the artwork.

Repairing the Past: Restoring Losses and Reframing for the Future

All losses and tears were repaired on the verso using Japanese tissue and wheat starch paste, both staples of modern conservation for their strength, flexibility, and reversibility. Smaller areas of loss were filled with paper-pulp infills, toned with pastel pencils to blend seamlessly with the surrounding surface. Larger fills were created using hand-toned Japanese tissue coloured with watercolour to match the paper’s original hue.

During treatment – toning in fills.

The portrait was then mounted into a new conservation-grade window mount and returned to its original cleaned frame, which now featured modern protective upgrades:

- Tru Vue Optium Museum Acrylic glazing, offering crystal-clear visibility while filtering ultraviolet light and reducing glare and static which can lift friable media from the paper surface over time.

- A Meridian board backing, designed for stability and acid-free protection.

- Frame sealing tape, creating a microclimate barrier against acetic acid and other VOCs from the wooden frame and gum tape to seal the back of the frame against environmental fluctuations and insect ingress.

This reframing not only preserved the historical integrity of the original frame but also ensured the artwork’s long-term stability under museum conditions.

Discoveries During Conservation

Every conservation treatment reveals something new about both the artwork and its history. In this case, these intriguing details came to light:

Hidden Media: Under magnification, Karina identified ink wash in addition to charcoal and pastel — evidence of Lanchester’s subtle layering technique to achieve tonal depth.

Family Intervention: Traces of an earlier re-framing were found — a note on the original mount board referred to the addition of a new plywood backing for 3 shillings. Likely requested by a family member decades ago. Ironically, that “modern” plywood later caused the very warping and acetic acid release that contributed to the damage, a reminder that even well mounted works on paper should be assessed and have their mounts refreshed periodically to safeguard the work. This section of mount was preserved and affixed to the back of the frame in a conservation grade melinex wallet as it is part of the artwork’s provenance.

The Artist: Mary Lanchester (1864–1942)

Though lesser-known today, Mary Lanchester was a talented British artist and printmaker active in the early 20th century. She studied at the Brighton School of Art and exhibited between 1896 and 1910, contributing to Britain’s growing movement of women artists working in print and design.

A colour woodcut print by Lanchester is held in the British Museum collection, linking her work to a broader lineage of late Victorian and Edwardian art that bridged traditional drawing and emerging printmaking techniques.

This portrait encapsulates her sensitivity to tone and character — the delicacy of chalk and pastel layered over the fluid depth of ink wash — and represents a compelling example of early 20th-century portraiture on paper.

Lessons from a Century of Materials

The conservation of this portrait highlights broader themes in paper preservation. During the industrial revolution, paper quality declined as wood pulp replaced cotton and linen rag. The high lignin content in these modern papers leads to acidification, embrittlement, and yellowing over time. Combined with acidic adhesives and wooden backings, many works from this period face similar degradation.

By contrast, contemporary conservation materials — acid-free, pH-neutral, and fully reversible — are designed to safeguard both the artwork and its history.

As Karina explains, “Our role isn’t just to restore the visual beauty of a work; it’s to slow its aging and protect it for future generations. Every material we use is chosen so the next conservator, decades from now, can safely intervene again if needed.”

From Studio to Fair: A Conservation Story Shared

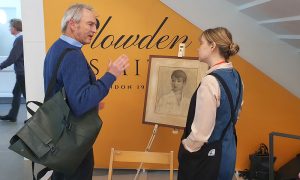

Visitors to the British Art Fair had the opportunity to see Karina in action and discuss conservation methods.

What made this project particularly special was its public nature. By performing parts of the treatment live at the British Art Fair, visitors could witness first-hand the precision, patience, and ethical decision-making that define modern conservation.

Philip Mould visited our stand at the Collectors’ Preview and discussed the details of our planned treatment with our paper conservator Karina.

At the LAPADA Fair, the fully restored Portrait of a Boy hung resplendent once more — its paper stabilised, its delicate tones visible through new glazing, and its story enriched by discovery.

The project stands as a reminder that conservation is as much about storytelling as science. Every mend, every cleaning decision, every fragment of residue tells part of an artwork’s journey through time — from the artist’s hand to the present day.

To find out more about our work we have more examples on our paper conservation page.

If we can help you with conservation of artworks, drawings, prints or historic documents please do not hesitate to contact us for a complimentary estimate and treatment proposal.